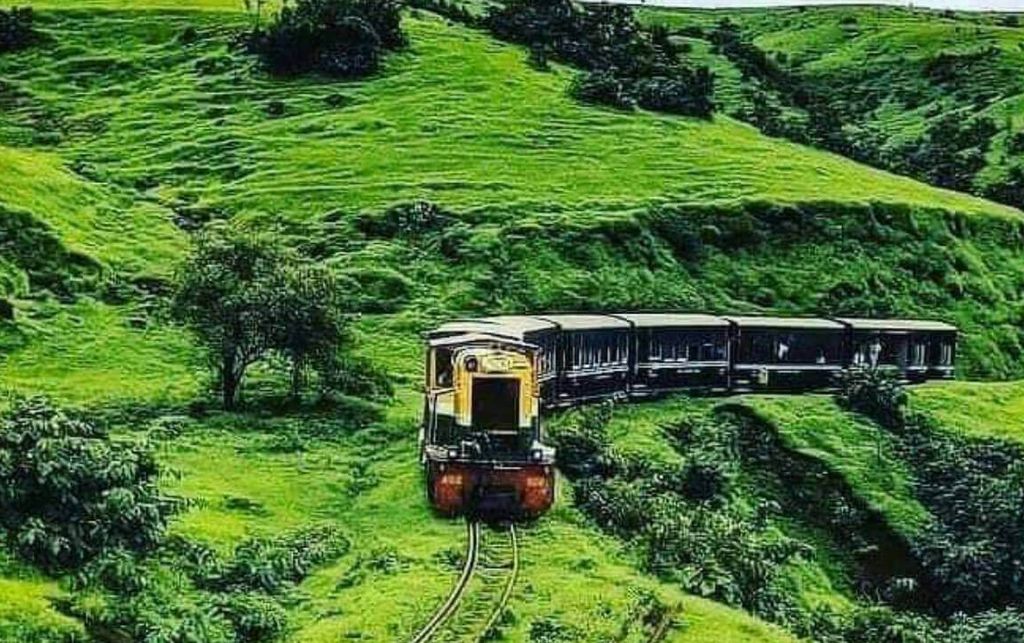

Embarking on an exploration of India’s enchanting hill trains unveils a tapestry of mesmerizing journeys through some of the country’s most picturesque terrains and cultural treasures. These iconic railways, adorned with heritage and scenic beauty, offer travelers a nostalgic and immersive experience that transcends mere transportation. From the captivating views of the Himalayas to the verdant landscapes of the Western Ghats, each hill train presents a unique passage through nature’s splendor and historic charm. Join us on a virtual voyage as we delve into the allure and rich heritage of India’s hill trains, each journey promising unforgettable vistas and cultural encounters that linger in the memory long after the adventure concludes.

1. Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (DHR):

History:

In 1878, Franklin Prestage, the Agent of the Eastern Bengal Railway, envisioned the practicality of establishing a railway connection between the hills of Darjeeling and the plains. His proposal was primarily motivated by practical economic factors, including the substantial cost disparity of essential goods between Darjeeling and Siliguri, the imperative need to transport tea for export, and the incapability of the existing road infrastructure to accommodate the burgeoning traffic. He presented a plan for constructing a narrow two feet gauge railway line from Siliguri to Darjeeling.

Presenting a comprehensive proposal to the Government of Bengal, which received approval from Lt. Governor Sir Ashley Eden, Prestage highlighted how implementing a railway system could significantly decrease transportation costs between Darjeeling and the plains. For instance, rice, priced at 98 rupees per ton in Siliguri, soared to 238 rupees at Darjeeling. He was confident that the construction costs for the 2 feet gauge rail-line would be manageable, and envisioned designing locomotives that, while compact, would possess adequate power to ascend steep gradients. On April 8, 1879, Prestage received the ultimate approval for his project and established the Darjeeling Steam Tramway Co. However, the initial intention of operating the line as a steam tramway was swiftly discarded. Instead, on September 15, 1881, the company opted for the title of Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Co. (DHR), a name that endured until the Government of independent India assumed control on October 20, 1948. Throughout this period, Gillanders Artbuthnot & Co., a venerable managing house in Calcutta, managed the financial, legal, and procurement aspects of the railway, playing a significant role in its operations and administration.

UNESCO World Heritage Site:

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (DHR) received its designation as a World Heritage Site on December 5, 1999, owing to several significant reasons. Firstly, the railway stands as an exceptional exemplar of the impact of an inventive transportation system on the social and economic progress of a multi-cultural region. Its creation was designed to serve as a model for similar developments globally, showcasing how the innovative railway system contributed to the area’s advancement. Moreover, the evolution of railways during the 19th century played a pivotal role in shaping social and economic progress worldwide. The DHR uniquely illustrates this transformative process in an outstanding and pioneering manner, highlighting the profound influence of railways on global socio-economic developments.

Features of DHR:

The entire route spans a distance of 87.48 kilometers. From Sukna to Darjeeling, there are no permanent signals, and the train movements are managed through manual hand signals. The intricate network of curves, loops, “Z” shapes, and steep inclines along the track represents a brilliant engineering feat, providing travelers with an enjoyable experience. The diminutive 19th-century steam locomotives, equipped with four wheels, are revered as living relics that evoke the sights, sounds, and nostalgic romance of a bygone era.

2. Kalka-Shimla Railway:

History:

The Kalka Shimla Railway was constructed during the period of British rule in India with the purpose of connecting Shimla, the summer capital of the British Indian rail network. This railway system has secured a place in the Guinness Book of World Records for its steep ascent over 96 kilometers, featuring the passage over 800 bridges and viaducts, establishing itself as one of the most picturesque hill railways in India. Regarded as the “crown jewel” of the Indian National Railways during the British era, the Kalka Shimla Railway (KSR), extending over 96.6 kilometers as a single-track operational line, was established in the mid-19th century to facilitate travel to the elevated town of Shimla. It signifies the technical and material endeavors aimed at linking mountainous regions through railway connectivity. Notable engineering marvels such as the world’s highest multi-arch gallery bridge at Kanoh and the world’s longest tunnel at Barog (during construction) underscore the remarkable engineering prowess employed to realize this ambitious project. The decision to establish the summer residence in the Shimla region by the Indian Colonial government, attributed to its healthier climate due to altitude, elevated the region’s political significance. Transport connectivity to the Himalayan foothills, Delhi region, and the Ganges plain became a crucial matter. Discussions about a potential rail link date as far back as 1847. Inaugurated in 1903, the 96-kilometer narrow-gauge Kalka-Shimla Railway, often referred to as the toy train line, was developed to connect Shimla, the erstwhile summer capital of British India, with the northern plains. Subsequently, carriages were manufactured for the Railway in the same year.

The Journey:

The railway line commences its ascent immediately upon departing from Kalka railway station. The toy train leisurely traverses the track, emitting its distinctive whistle as it passes through an array of forests including deodar, pine, oak, and maple, maintaining a gentle pace of 22 kilometers per hour. Embarking on this journey unveils a remarkable transition in vegetation, showcasing the grandeur of the railway stations and Gothic-style bridges scattered along the route.

One of the most rejuvenating aspects of this expedition is the opportunity to sit beside the window, inhaling the refreshing breeze and immersing oneself in the lush greenery. The journey offers a delightful scent of fresh dew on the foliage, the melodious chirping of birds, and picturesque scenes of cattle grazing alongside the track. This experience is particularly invigorating when traveling aboard either of the two early morning toy trains, providing a serene and captivating encounter with nature’s tranquility.

3. Nilgiri Mountain Railway (NMR):

History:

In 1854, initial plans were laid out for the construction of a mountain Railway stretching from Mettupalaiyam to the Nilgiri Hills. However, bureaucratic hurdles prolonged the process, leading to a 45-year delay before the completion and installation of the line. Eventually, in June 1899, the construction culminated, and the railway became operational, initially managed by the Madras Railway through an agreement with the Government. The Madras Railway Company oversaw the management of this railway on behalf of the government for an extended period until it was later acquired by the South Indian Railway company. An extension of the line from Coonoor to Ootacamund was accomplished around 1908, maintaining the same gauge over an 11- and 3/4-miles distance at a cost of Rs. 24,40,000. Notably, the steepest gradient along this route stands at 1 in 23, and unlike the section between Coonoor and Mettupalaiyam, there is no rack system in place to aid traction.

Features of NMR:

The railway line spanning from Mettupalaiyam to Ooty measures 45.88 kilometers in length, traversing through both Coimbatore District and Nilgiri District in Tamil Nadu, situated on the eastern slopes of the Western Ghats. Mettupalaiyam is positioned at the foothills, boasting an elevation of approximately 330 meters, while Udagamandalam, commonly known as Ooty, rests on the plateau with an altitude of 2200 meters. The average gradient along this railway line is approximately 1 in 24.5, indicative of the gradual ascent and the varying altitudes encountered throughout the journey.

The maximum permitted speed on the Mettupalaiyam-Kallar and Coonoor-Udagamandalam “Non-Rack” sections is 30 kilometers per hour. However, between Kallar and Coonoor on the “RACK” section, the maximum permissible speed is restricted to 13 kilometers per hour due to the differing operational requirements of this particular stretch. The Nilgiri Mountain Railway region experiences rainfall during both the south-west and north-east monsoons. The average annual rainfall measures around 1250 mm at Udagamandalam, 1400 mm at Coonoor, and 500 mm at Mettupalaiyam. Despite encountering these varying degrees of rainfall, the Nilgiri Mountain Railway continues to chug along, demonstrating its resilience and ability to operate even during downpours.

4. Matheran Hill Railway:

History:

The construction of the Matheran Hill Railway was led by Abdul Peerbhoy and was financed by his father, Sir Adamjee Peerbhoy of the Adamjee Group. The route was designed in 1900, with construction beginning in 1904 and completed in 1907. The original tracks were built using 30 pound per yard rails but were later updated with heavier 42 pound per yard rails. Until the 1980s, the railway was closed during monsoon season due to increased risk of landslides, but it is now kept open throughout the year. The line is administered by Central Railways.

Features of Matheran Hill Railway:

The Matheran Hill Railway spans a 20-kilometer (12 miles) distance connecting Neral to Matheran in the Western Ghats. An exceptional characteristic of this railway line is its horseshoe-shaped embankments. The journey showcases various notable landmarks along the route: the inaugural Neral Station, the Herdal Hill segment, the steep ascent of Bhekra Khud, the solitary One Kiss Tunnel (nicknamed for its length allowing a quick kiss exchange), an obsolete water pipe station, the challenging Mountain Berry area featuring sharp zigzags, the scenic Panorama Point, and the terminus at Matheran Bazaar. Running in proximity to the Matheran Hill Railway, the broad-gauge railroad between Mumbai and Pune intersects at two points. The railway’s prevailing gradient stands at 1:20 (5%), necessitating a maximum train speed of 20 kilometers per hour (12 mph) due to the tight curves encountered along the track.

5. Kangra Valley Railway:

History:

The conception of the railway line was formulated in May 1926, and it was officially inaugurated and put into operation in 1929. This line encompasses two tunnels, one measuring 250 feet (76 meters) in length, while the other extends to 1,000 feet (300 meters). Due to the employment of smaller and less potent engines on this narrow-gauge line compared to those used on broader gauge main lines, the design aimed to circumvent steep inclines. To achieve this, rather than costly and direct tunneling through the mountains, an alternate route further to the south with a longer right-of-way was chosen. This strategy allowed for more gradual slopes along the track. Between 1942 and 1954, there was a hiatus in train services to the east of Nagrota. During the construction of the Maharana Pratap Sagar, alterations were necessitated along the railway line between Jawanwala Shahr and Guler. The rerouting occurred to higher ground along the eastern shore of the newly formed reservoir. Subsequently, in 1973, the segment encompassing these two stations, including Anur, Jagatpur, and Mangwal stations, was abandoned. A new alignment was established, featuring several newly introduced stations, which commenced operations three years later as a replacement for the discontinued section.

Features of Kangra Valley Railway:

The Kangra Valley Railway, situated in the sub-Himalayan region of the Kangra Valley, spans a total distance of 164 kilometers (101.9 miles) from Pathankot, Punjab, to Jogindernagar in Himachal Pradesh, India. This railway line falls within the jurisdiction of the Firozpur division of Northern Railway.

Ahju station stands as the highest point along this route, situated at an elevation of 1,290 meters (4,230 feet) above sea level. Daily operations include six trains departing from Pathankot, with two trains traveling up to Joginder Nagar and four trains terminating at Baijnath Paprola.

As our exploration of the enchanting hill trains of India draws to a close, we are left awestruck by the vivid tapestry of natural beauty, cultural heritage, and nostalgic charm these railways offer. From the UNESCO World Heritage-listed Darjeeling Himalayan Railway to the scenic routes of Kalka-Shimla, Nilgiri Mountain Railway, Matheran Hill Railway, and Kangra Valley Railway, each journey has unfolded a captivating narrative of India’s diverse landscapes and rich history. The rhythmic chugging of the engines, the mesmerizing vistas passing by, and the glimpses into local life along the routes have left an indelible mark on our memories. These hill trains, embodying a blend of heritage and scenic delights, stand as an ode to India’s timeless legacy of railway engineering and continue to beckon travelers to embark on these nostalgic voyages, promising unforgettable experiences that linger as cherished reminiscences of our explorations.